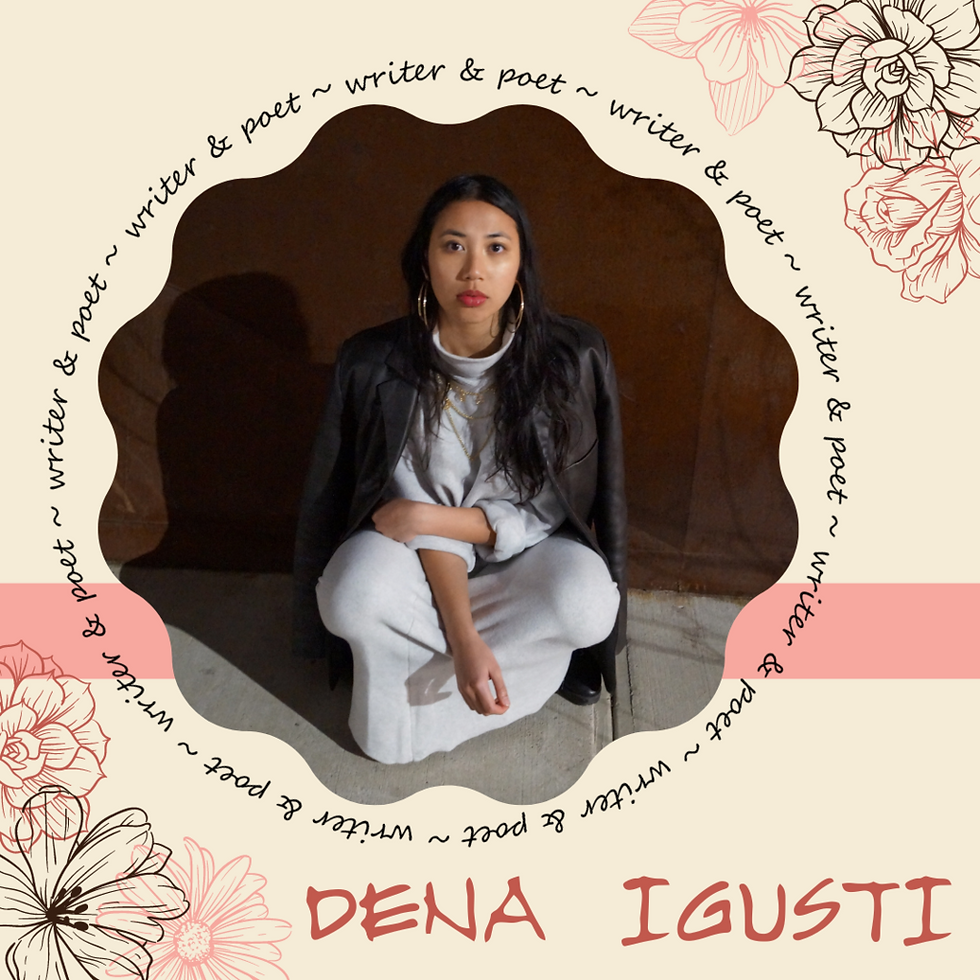

Interview: Dena Igusti (she/they), queer Indonesian Muslim poet, playwright & journalist from Queens

- Sep 12, 2020

- 7 min read

Article by: Joyce Keokham

Graphics by: Krithika Subramanian

Dena Igusti (she/they) is a queer Indonesian Muslim poet, playwright, and journalist based in Queens, New York. She is the co-founder of Asian multidisciplinary arts collective UNCOMMON;YOU and literary press Short Line Review. Her debut book Cut Woman is out now.

CW: FGM

There are few things attractive about Facebook but having found those few things, I log in often. I’m allured by the access to communities hosted on the platform rather than the platform itself. In a facebook group I cherish, SAD & ASIAN, I find myself connected to marginalized Asians everywhere in the world.

It was in SAD & ASIAN that I encountered poet and playwright Dena Igusti (she/they) who was celebrating the publication of their book Cut Woman. Dena describes Cut Woman as a collection of poems discussing the navigation of grief, loss, and anticipated mourning as an Indonesian Muslim survivor of female genital mutilation. After congratulating Dena, I reached out to profile them for the Homegirl Project.

Aware that I’ve never met anyone living at Dena’s intersection, Indonesian Muslim survivor of FGM, I anticipated learning without realizing how much I could relate. Quite literally, Dena is the neighbor next door. A zoom call connected us from Brooklyn to Queens, where Dena is a native, allowing us to discuss Cut Woman and the influences that led Dena to write it.

Like most young Americans, Dena contemplates their diasporic background while traversing between the languages and cultures which become blended parts of us. Dena is among an emerging class of writers who do not and could not ‘other’ their own experiences by italicizing and/or footnoting them. With impeccable grace Dena ties poems titled self portrait as the blunt in his mouth and self portrait as kuntilanak into the same cannon. I’ll help this once: Kuntilanak is an Indonesian folklore spirit known to be a malicious and carnivorous flesh eating female vampire ghost.

As many diasporic children also do, Dena questions and criticizes the self-appointed roles of white saviors. The complexities of having dual identities are reflected in the sharpness of Dena’s words and Dena’s words are sharpened by their courage to be vulnerable.

In altar, Dena poses

“...a country i was never supposed to step foot in // gives me words

for what was never // supposed

to happen to me // so i feel obligation //

invite America in // white reporters and “saviors”

pour in by the dozens // break in everything in sight //

i ask // why have you ruined

everything? ...”

This is a point Dena drives home in their work. With reason, they have become wary of white spokespeople who speak on behalf of female genital mutilation as an extension of their xenophobia. Dena says “People use it as a way to justify or affirm their own racism and Islamophobia. Like ‘See!! Look what they made you go through!’. If I don’t have the full language to understand my own experience, they definitely don’t.”

Dena’s circumcision happened when she was 9 years old. With 11+ years to process, Dena’s debut book voices the complex emotions which follows their experience with FGM. Their effort to share and express the intricacies of their trauma manifests in an exploration between mediums. In Cut Woman there are pieces like sunat: a recollection (in the wake) which reads as a one act play, listening to ‘At Your Best’ underwater (an erasure) adapts Aaliyah’s classic ballad into a sensory experience, and transmission in waves (to be read to jhene aiko’s “new balance”) a poem which demands a score.

Read Cut Woman. Witness the tools, the languages, the references, all of which Dena employs to convey the cultural intricacy of their trauma. When Dena says white people aren’t qualified to speak on their behalf, believe them.

In Dena’s own words,

Jk for the homegirl project: Before Cut Woman I never thought about separating ‘myself’ from my body. They were always the same entities. In staircase g, or the warmth pressing on your forearms the way he won’t you had this great line “to instead have both of us spoken about // —in the same breath— // —in the same name—” It became a running theme where for you there is a separation from the body but the world keeps associating it together.

DENA IGUSTI: That’s one of the things I wanted to get at with this book. I think because of the ways in which trauma was inflicted on me, it felt weird seeing myself and my body as one entity. The physical harm that has been done to my body is just very separate from the ways which I processed it myself.

I am a survivor of female gender mutilation, when it happened I was 9 years old. But I didn’t process that trauma for 10-11 years because it was completely normalized in my family. So I was completely “fine“ for a very long period of time. I was in denial thinking this was normal but for my body, there was very real harm. Not only in terms of the physical aspect of the clitoris being cut, but there was such a shame and guilt around noticing anything sexual, my body would flinch and be suspended, at a complete halt.

There were very real things in terms of trauma that happened to me but I didn’t just didn’t process that and because of that, I felt like I had to separate myself as two separate entities.

Jk: Were you able to communicate your experience with elders who have also been through it like your mother or grandmother?

DENA IGUSTI: My aunt went through it, my grandma went through it, my mom went through it. We all went through it with the basic premise that FGM is this false sense of protection. There was this fear that although I am Indonesian and Muslim, I am also an American girl,they thought I would be influenced by America and get into some trouble with some boy, get pregnant and then something bad will happen. That’s how they always saw it. Do this so that you don’t get sexual urges. It was just so normalized for the elders.

Most Indonesians don’t go through it, most Muslims don’t go through it whatsoever but because they grew up with such a stigma talking about genitalia they were in a similar position as me. They knew their family went through it and they thought it was fine because all their elders thought it was fine.

After it all went down, they kept telling me I was fine. Then I started having this idea that if I felt like I was hurt, it felt subconsciously like it was rooted in me being American. Feeling my trauma, my pain, was a westernization that my own family elders didn’t have at all. There was this guilt of like, oh maybe I’m not strong enough. Maybe I’m too American.

Jk: In altar you write how “you thought finishing one of my sentences // gave you // right // to crowd // the dancefloor and block the entrance?” which is how you feel about Americans who try to speak for you. So I wonder how the matriarch in your family feels they hear how Westerners speak on female genitialia mutilation?

DENA IGUSTI: My mom and aunt undermine the pain a lot. They undermine the severity of it. And I do acknowledge that that is their own form of coping. But they see it as a prick, or a small cut. That’s all they call it.

There’s so much language and shaming that comes with FGM. There’s a before and after process with it. I didn’t know when it was going to happen to me or that it was going to happen. But I heard comments like “she’s getting bigger now” or “oh she might like boys now.”

Jk: That’s such a disgusting symptom of patriarchy!

DENA IGUSTI: That’s another thing, how circumcision goes for both genitalia. If you have a penis, and you’re considered a boy, they give you money! You have a party! People will dap you up and hug you.

For me, I was crying and I couldn’t walk for a long time. And it was quiet… They rushed and hushed me in and out of the taxi and told me not to cry because people could hear. It was an isolating feeling. I felt a sense of guilt for even having a vagina and causing this burden on my family, for them to have to do this for me.

Jk: Wow. How do they feel now that this is one of the main topics that you write about? How do they feel that you are coming out with a book on this specific experience?

DENA IGUSTI: Here’s the thing…. They don’t know. I’m going to figure this out after the publication date.

(We both laugh at this.)

DENA IGUSTI: They like to google me though. My aunt found sunat online and had a very peculiar reaction where she was just grossed out like “Eww. You’re talking about your genitalia?” She couldn’t see the trauma of it. For her it feels like you’re being promiscuous just by mentioning it.

Jk: You’re breaking so many walls of generational fears and shame! I also enjoyed how easy you can go from one dialect to another, between pages or even within the same poem. It shows that even as you acknowledge what was done to you physically hurt, it’s beyond the Western media's portrayal of it. You write on all the layers of it without othering it.

DENA IGUSTI: The reality of being bilingual is that it’s all mixed together. Also how language works, I don’t know how to explain it but you don’t take definitions of words seriously. Especially in English, if I see one word, I’m just going to interpret it as something else.

I want to portray that a lot more with the book because they do bleed into each other. There isn’t this clear distinction. I think people who don’t experience being a multicultural kid, don’t realize there isn’t a hard line.

Jk: There isn’t a hard line–and lines curve! Okay, last question. What do you hope that Cut Woman will do for those who read it?

DENA IGUSTI: I can think of things that I don’t want it to do. I don’t want people to feel terrible. I don’t want an Indonesian kid to see my poetry for the first time and all they see is pain and drama. I don’t want people to feel bad about their community.

I also don’t want to get the white lady who cries on my shoulder and tells me I’ve been through so much. Or for people to use it as a way to justify or affirm their own racism and Islamophobia.

What I want it to do ultimately is let people kind of disperse binary and boundary and understand the ways in which we navigate things all seep into each other. There are never set stages in life or in death.

I want people to understand how to interrogate the before and after. What does it mean to live in the moment right before you realize everything else isn’t going to matter? What is it like living in that exact moment right before the actual aftermath of whatever you experienced?

Comments